In the early days of Nexus, our concerts were totally improvised featuring many non-Western percussion instruments that we collected. John Wyre was an influence on all of us as he brought instruments from his travels to Asia to our improv sessions. I began scouring antique stores, import shops, and yard sales and discovered a few unusual instruments, but when Nexus began touring Japan, I found some of my favorite instruments to use in our free-form concerts.

The instruments we refer to as Japanese temple bowls were some of my first purchases. In 1976, Nexus members visited a Buddhist temple supply store in Kyoto, and we all bought several temple bowls. As we were paying for our instruments, the owner of the store gave each of us a small silver temple bowl as a thank-you gift; I still use this bowl in Nexus improvisations. I drilled a hole in the center of the bowl and attached a length of sash cord to it so I could strike the bowl and swing it in the air producing a pulsating resonance. All of us in Nexus treasured our little temple bowls. In fact, a few years later we were on a tour of England and happened to play a concert in Nottingham. Bill Cahn’s bowl cracked during the concert and he couldn’t use it anymore. In order to honor the spirit of the bowl, Bill traveled to nearby Sherwood Forest the following day and buried his temple bowl with proper ceremony.

Small Japanese temple bowl

On another Japanese tour, I spent a free afternoon wandering around Kyoto and happened upon a store that appeared to be an antique store. In it, I found two instruments that I had never seen before and purchased both of them. One of them was a pair of 9” long wooden blocks with some Japanese

Fire warden blocks

characters painted on them. When I returned to our hotel, I asked our host, Toru Takemitsu, what these blocks were used for and what the inscription said. After examining the blocks for a long time, Toru said these particular blocks had been used in the past for a fire warning in Japanese villages. Back then, houses were made from highly flammable materials and lanterns were used for lighting. In the evenings, a fire warden walked through the streets clapping these blocks together to get the attention of residents, reminding them to extinguish their lanterns and cooking fires before they retired for the night.

Kabuki blocks

Toru continued to tell me that these blocks are called hyoshigi and are now used in Kabuki theater performances. I found several sizes of these hardwood blocks in a shop in Tokyo.

My second exciting find in the Kyoto antique shop was a ring bell. Toru explained that this was a horse bell, and I assume he meant that horses had a rope around their necks with this bell on it much the same way as cows have a cowbell attached to them. There is a metal pellet in between the two halves of the bell, and I found I could create interesting rhythmic grooves by shaking the bell back and forth.

Japanese ring bell

(top view)

Japanese ring bell

(side view)

These ring bells must have another purpose because I found them for sale in a Buddhist temple supply store in the Asakusa area of Tokyo and bought three of them. I have visited this large temple supply store many times over the years. It is in an interesting location diagonally across the street from the Japanese Drum Museum and close to Komaki Music’s Japanese Percussion Center where traditional Western percussion instruments are sold. It is also near the beautiful Sensō-ji temple, the oldest Buddhist temple in Tokyo.

Buddhist Japanese ring bells

African ring bell

I was particularly surprised to find these Japanese ring bells because a few years earlier I found a group of small dark grey ring bells in an antique shop in rural Connecticut. The shop owner said they were African bells. I bought all of them and gave one to each member of Nexus. I had never seen ring bells before, so it was exciting to find another version of them in Japan.

I have another ring bell that I got from John Wyre. This one is a gold color and larger than the dark grey ones. It is supposedly from Ethiopia.

Ethiopian ring bell

In the 1970s, I was driving along Route 7 in western Connecticut and spotted an antique shop along the side of the road. I stopped in to see what they had and was surprised to find several very large Japanese temple bowls for sale. I bought the largest one I could afford at the time; it is almost 16” in diameter and has a strong C3 pitch. I have used this temple bowl in many Nexus improvisations and also in a composition of mine called Cadence. Canadian composer, Claude Vivier, wrote specifically for this temple bowl in his solo percussion work, Cinq Chansons.

Large “C3” Japanese temple bowl

Japanese temples have many shapes and sizes of bells and they often sell replicas in gift shops. I collected several of these bells that always seem to come in a green color.

Small green Japanese bells

One of my favorite shapes for a bell is this one that I found in a shop in the Shibuya area of Tokyo.

Japanese bell

On one of my last trips to Japan with Nexus, Garry Kvistad and I found a small temple supply store in a covered mall in Fukuoka where we discovered this unusual gold bell. The dome-shaped bell rests on a base with a pole that extends to the center of the bell. The bell comes with a small mallet for striking.

Gold Japanese bell

Japan has more than just bells. Bill Cahn and I found this cymbal-playing chicken in a convenience store in Kumamoto, and of course we each had to get one.

Chicken playing cymbals

In 2010, Nexus performed the Takemitsu concerto From me flows what you call Time with the Hyōgo Performing Arts Center Orchestra in Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan, conducted by Yutaka Sado. At the conclusion of our series of concerts, Maestro Sado presented each member of Nexus with a toy replica of himself.

Yutaka Sado toy

Speaking of From me flows what you call Time, Garry Kvistad, in consultation with Toru Takemitsu, designed the wind chimes that are used as an integral element in the concerto. The piece has a Tibetan theme, and Garry created a Tibetan Prayer Chime using the five-note motif from Takemitsu’s composition. You can see and hear the wind chime on this page from Garry’s Woodstock Chimes® company website. Garry also explains about the Tibetan wind horse and its relation to the Takemitsu concerto.

https://www.chimes.com/products/tibetan-prayer-chime?_pos=1&_psq=tibetan%20chimes&_ss=e&_v=1.0

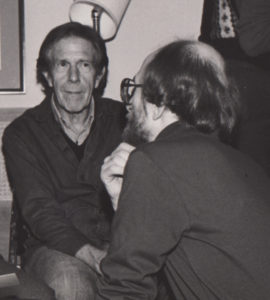

Nexus with Toru Takemitsu in Carnegie Hall

Some of the most magical bell sounds in Japan come not from bells but from a living source. During our stay in Hyōgo for our Nexus concerts with Maestro Sado’s orchestra, Bill Cahn, Garry Kvistad and his wife, Diane, and my wife, Bonnie, and I spent a free day in nearby Kyoto. After a very hot day of sight-seeing, we decided to dine at Toru Takemitsu’s favorite sushi bar located near the famous Tawaraya ryokan. Toru had taken us to this sushi restaurant many years earlier and we looked forward to a return visit. As we sat at the very small bar eating delicious sushi and drinking sake, we noticed bells ringing. At first, I thought they were bells at the entrance to the restaurant indicating that new customers were entering, but there were no new people coming in for dinner. Then I remembered that some Japanese restaurants have subtle sounds of nature piped in instead of music, so I thought it must be a recording. I asked our kimono-clad waitress what the bell sound was. She smiled, went away for a minute and returned with a cage full of suzumushi – crickets that make a sound just like small, tinkling bells. I was surprised that after many trips to Japan, no one had told us about these crickets that made such a beautiful bell-like sound. The next day at our rehearsal in Hyōgo, I asked a Japanese percussionist about suzumushi and she said, “Oh, we have those in our backyard; they are really noisy!” I still think they produce a beautiful sound. You can see and hear for yourself here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=26ohzqVVjY0

The two bells pictured here are not Japanese, but they have a connection to Japan.

Ryoanji bells

The wooden bell is a water buffalo bell from either Myanmar or Indonesia. The metal bell is a large cowbell, possibly from Switzerland. I found both of them in antique stores in Connecticut. When I bought the cowbell, it had an abandoned wasp’s nest fastened on the inside-top of the bell. Wasps must attach their nests strongly because the nest stayed there for many years’ worth of performances before it eventually fell out. The brown cowbell has a darker sound than the almglocken that are commonly used these days. When I was asked to record John Cage’s composition, Ryoanji with flutist, Robert Aitken, I met with Cage to ask him what I should use since the part doesn’t indicate specific percussion instruments. In the score for the piece, which was inspired by Ryōan-ji, the famous dry landscape rock garden in a Zen temple in northwest Kyoto, Cage says this about the percussion part:

“At least two only slightly resonant instruments of different material (wood and metal, not metal and metal) played in unison. The playing begins anywhere about two measures before the instrumentalist or vocalist, continuing during silences between two songs or pieces, and ending about two measures after the instrument or voice has stopped. These sounds are the ‘raked sand’ of the garden. They should be played quietly but not as background. They should even be imperceptibly in the foreground. They should have some life (slight changes of imperceptible dynamics) as though the light on them is changing.”

John Cage and Russell

I showed Cage a wide assortment of my instruments and he selected these two bells. You can read more about this piece and the evening I spent with John Cage in my article “Encounters with John Cage” here:

https://www.nexuspercussion.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Encounters-with-John-Cage.pdf

Toru Takemitsu taught me a new way to approach improvisation in music. One of the elements of Japanese music that he talked about when comparing the Japanese and Western approaches to music making was the concept of ma. In his article, “Toru Takemitsu, on Sawari,” in Locating East Asia in Western Art Music (Y. U. Everett and F. Lau, eds.), he wrote:

“[P]eople feel a sense of transience in the interval between strokes. Japanese music possesses a distinct kind of space [ma]. To give you a familiar example, in Noh drama there is a tensed space after one or other of the drums…is struck before the next sound occurs. Practitioners of hogaku typically talk about making the most out of ma, to make it ‘come to life’….To bring ma ‘to life’ means to make the most of the infinite sounds that exist between two performed sounds…. Instead of communicating solely through the actual sounds that are performed, in Japanese music the space created between realized sounds plays a significant role. I think this is an important and highly elusive characteristic of Japanese in comparison to modern Western music.”

I cite Takemitsu’s article in my book Performance Practice in the Music of Steve Reich  and add this description of my experience with improvisation in Takemitsu’s music:

and add this description of my experience with improvisation in Takemitsu’s music:

“Takemitsu sometimes wrote improvisatory elements into his compositions: the opening crotale sequence as the percussionists make their entrance in From me flows what you call Time; the imitation of rain drops by the crotales in Rain Tree; and the completely improvised piece, Munari by Munari with very little actual notation at all, only a score of colored paper cut into different figurations and a few enigmatic written phrases. I find it extremely difficult to perform these improvisations, especially the crotale passages in From me flows what you call Time and Rain Tree, with the appropriate sense of ma. My inclination as a Western-trained musician is to attempt to coordinate my crotale attacks with something else going on in the music or in relation to crotale sounds played by the other players. For me, it requires a determined attempt at disassociation to achieve the correct feeling of ma. Takemitsu explained to me that the percussionist who, in his opinion, played most successfully with a sense of ma was Yasunori Yamaguchi. He said Yamaguchi placed sounds in such a way that the sounds and the space between the sounds had the same sense of importance.”