Further to emailed inquiries on the subjects of percussion performance and instruments, one recent inquiry was seeking advice about support structures for gongs.

This topic is right up my alley. I’ve always had a fascination with pitched gongs and unpitched tam-tams, probably inspired by John Wyre, a colleague in NEXUS until his passing in 2006. As with any support structure for percussion instruments, the goal is always to have it allow the percussion instrument to make the most desirable sound possible.

In the early days of NEXUS, following John Wyre’s lead, I tried to accumulate as many gongs as possible to use them for their exotic sounds in NEXUS improvisations. In the 1970s it wasn’t possible to simply open a catalog or go to a website to purchase new gongs, and there was virtually no place to obtain them, short of traveling to Asia.

But there was a way to find gongs, mostly by finding them in antique shops. Travelers to Asia in the early 20th century and North American soldiers in the World War II and the Korean War had returned to their homes with gifts and souvenirs – including bells and gongs – from their travels and adventures. Eventually, the instruments ended up in estate sales and with antique dealers. The good news for us in the 1970s was that Asian bells and gongs were not generally valued; no one wanted them, so the prices were very low – $5.00 for small gongs to $50.00 for larger ones. Of course, finding gongs was still a matter of luck in walking into the right antique shop at the right time. And the specific pitch of any found gong had to be accepted as it was.

Also, because tuned gongs were generally not available, composers were not yet writing pieces that utilized them. Curiously, when percussion parts were scored for gong, more often than not, what the composer really intended was the sound of an unpitched tam-tam.

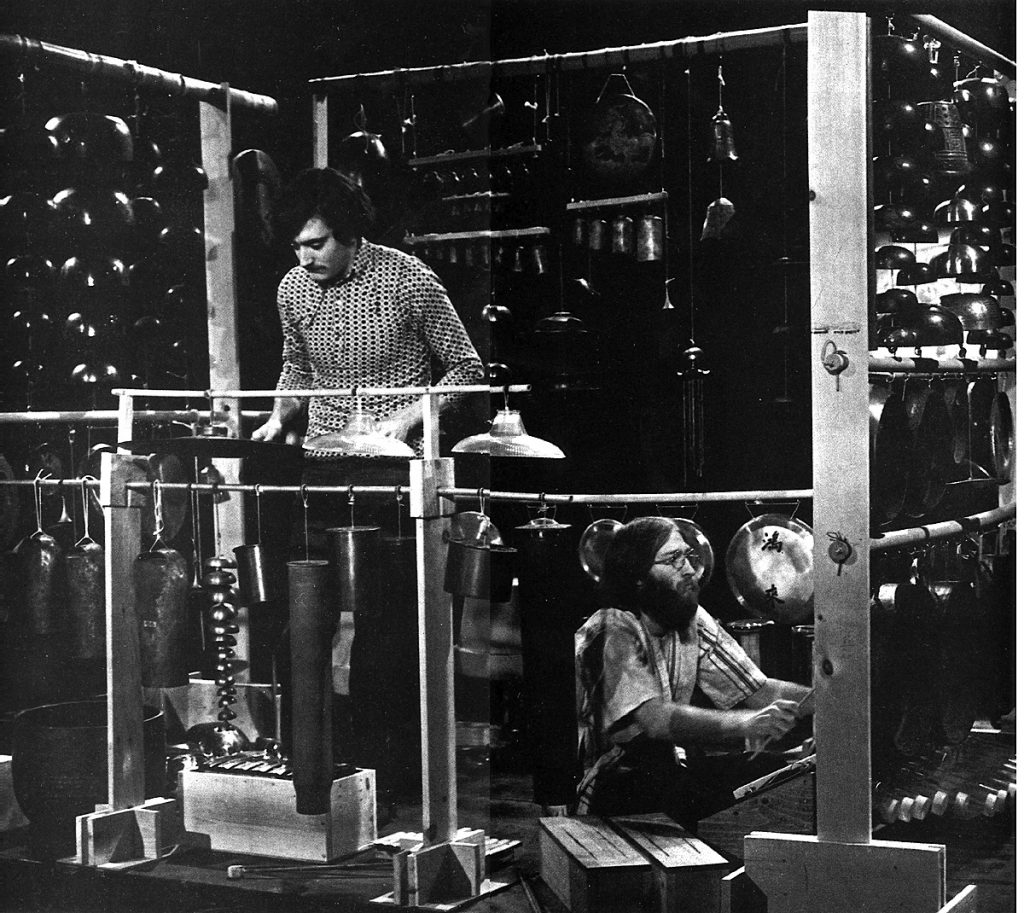

Having eventually acquired a collection of gongs from assorted cultures, the issue for those of us in NEXUS was how to best suspend them. Our initial solution was a system of wooden racks with two posts supporting two or three rails, from which the gongs could be suspended. Screw hooks were attached to the rails for specific gongs, so that each gong – having only a single cord – could be suspended from two of the screw hooks. (see Photo 1)

One problem that became evident was that the placement of screw hooks on the rails was fixed for specific gongs of varying sizes, which made setting up and tearing down the gongs at performances somewhat inefficient. Furthermore, each of us in NEXUS would bring different instruments with us for every concert to use in the improvisations, so the fixed screw hooks for specific gongs were not necessarily well positioned on the rails for different sizes of gongs.

John Wyre’s very practical solution was to replace the single cord of each gong with two looped cords – one long loop through each of the two cord holes on every gong. (see Photo 2)

Each of the two loop-cords was then fitted with a wood dowel. During the setup it was quick and easy to simply place each looped cord over and around the top of the rail and insert the dowel back between the strands of its own loop-cord. (see Photo 3)

Another advantage to this system was that any gongs that were prepared in this way could be conveniently placed anywhere on the rail. And because the rails didn’t need screw hooks, they were much easier to pack and transport. (see Photo 4)

I copied John’s system to suspend my gongs, but instead of using dowels I used ‘s’ hooks on each of the two cords on each gong. (see Photos 5 & 6)

Today, with the ease of locating and obtaining gongs, composers are comfortable including them in their scores. In student solo recitals I have occasionally noticed a gong suspended on a boom cymbal stand in a way that allowed the gong to swing with a sideways rotation back and forth. The reason was usually to use the boom stand to position the gong in a convenient location in a multiple percussion setup. (see Photo 7)

The problem sometimes was that a swinging gong could make unwanted sounds, even swinging around to hit its own boom stand. Hanging a gong from a single point will always present this risk. To be more stable, a gong should be suspended from two points that are ideally directly over the suspension holes in the gong. John Wyre’s system – with a separate suspension cord for each of the holes – always makes this possible. (see Photo 8)

When a multiple gong array is required, it will be necessary to construct a support rack that is strong, easy to setup and take down, and as lightweight as possible for traveling and shipping. There are four systems I have used, each having its own positives and negatives.

Wooden Racks

When NEXUS started out in the early 1970s, pine wood gong and bell racks were used because the wood was relatively inexpensive, and time was available to construct the wooden support stands from 1”x3” or 1”x 4” knotty pine boards. And because we mostly drove ourselves to our performances in our own cars, we didn’t have to use road trunks to protect our instruments, stands and racks. (see Photos 9 & 10)

However, in time it became apparent that the wooden racks were bulky and heavy. Another system was needed so that the racks would be lighter in weight and less bulky to fit into road cases for transport by the airlines.

Speed Rail Aluminum Pipe Fittings

A good solution was found by using ¾-inch i.d. (inner diameter) Speed Rail pipefittings for 1-inch o.d. (outer diameter) aluminum tubing. This enabled the structure to be lighter in weight and easier to pack for touring. I first became aware of Speed Rail fittings after seeing them on Alan Abel’s bass drum cradles. After a little research I discovered the ‘U’ cross fittings, and they were simple – only one set screw instead of two for each cross fitting – and perfect for a gong rack. However the Speed Rail system was more expensive and the fittings needed allen wrenches to secure them. (see Photo 11)

Galvanized Pipe

Another system was used, not only for NEXUS, but also for the Rochester Philharmonic’s 40-inch Wuhan Tam-tam. Galvanized pipe and fittings are available at most hardware stores, and the prices are reasonable. Galvanized pipe and fittings are considerably heavier than the aluminum Speed Rail version, so galvanized racks will be more expensive to transport by airfreight, but the galvanized pipe system is as sturdy and durable as the Speed Rail system. (see Photos 12 & 13)

Photo 13 – base od a galvanized rack, showing two ‘els’ (elbow fittings) on the ends and one ‘tee’ fitting in the center

Ultimate Support (telescoping)

The best (and most expensive) light weight aluminum pipe and fitting system for gong racks was manufactured by Ultimate Support, a music accessories company based in Loveland, Colorado. Unfortunately, Ultimate Support no longer carries the needed pipe and fittings in its catalog. One great feature of the Ultimate Support rack system was the ability to telescope the pipe. So by having a 4-ft. length of 1-1/2-inch o.d. aluminum pipe telescoped into a 1-5/8-inch o.d. pipe, it is possible to have a rail length of 7-1/2-ft for use in a performance, that can collapse down to only a 4-ft length for packing and shipping. (see Photos 14, 15 & 16)

Photo 15 – Closeup of Ultimate Support telescoping fitting with 1-1/2-inch o.d. aluminum pipe (foreground) and 1-5/8-inch o.d. pipe (rear)

Photo 16 – Base of Ultimate Support rack showing casters (added separately) and ‘tee’ fitting in center

PVC Conduit and Fittings

Another lightweight system using PVC conduit and fittings was used to create fixed-size rack/frames for fixed-groupings of small gongs. PVC materials can also be found at most hardware stores at reasonable prices.

The PVC is not as durable as aluminum, and the flexibility of the conduit makes it impractical for heavier gongs and bells. On the road, however, the possibility of stacking frames of 4 to 6 small gongs into a road trunk is very practical. It’s best if the conduit is attached at each fitting with PVC cement AND a small bolt through a drilled bolt hole. (see Photos 17 & 18)

Photo 18 – Closeup of PVC frame/rack; note the bolt heads at each point where the conduit is attached to a fitting

Finally, I’ve been fortunate in NEXUS to have played repertoire for which all of the rack systems were used (and continue to be used, for music as diverse as Takemitsu’s “From me flows what you call Time” to Ellen Taaffe Zwilich’s “Rituals” to numerous NEXUS free form improvisations. (see Photo 19)

Thanks this is the most helpful gong hanging information I have found!! Know anything about gong alloys?