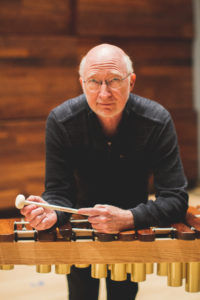

Bob Becker

In 1997-98, I conducted a series of interviews with percussionists to discuss their thoughts on rhythm. The following is an excerpt from my interview with Bob Becker that took place on February 6, 1998 while Nexus was on tour in Des Moines, IA.

Early Rhythmic Study

RH How did you develop an accurate sense of time when you were a kid?

BB The first thing I remember about that is when my grade school band director, Amy McConnell, made everyone in the band bring a sponge and a rubber band. You would fasten the sponge to the sole of your foot, and she would demand that everyone tap their foot to the time signature of every piece in the concert, all the way through. Since there were a hundred and some kids in the band, that would have been incredibly noisy, so that’s why she came up with the sponge technique. She was the band director and also the teacher for each individual instrument. She maintained that approach through everything she taught in all classes, so it was a big deal in her teaching. For a long time, that’s all I remember coming from a teacher who really addressed the issue of maintaining some kind of accurate time. When I got to college, my first couple of lessons with Bill Street got into triplet rhythms, for some reason. He had a collection of duets he had composed called “Dovetailing.” They were rhythmic duets for snare drum and were fairly complex with spaces or gaps in the rhythms. One part would fill in against the other. I had difficulty with those, at the time, and it made me interested in working on that. That doesn’t really address a steady accurate sense of time exactly, but I was aware that the technique or practice of subdividing the rhythm into smaller units was something I wasn’t too good at, so I tried to get all the books I could to work on it.

RH Snare drum books?

BB Yes, most of them were snare drum books. Bob Tilles had a good one on that topic [Practical Percussion Studies, Adler, 1962].

RH I associate him more with vibraphone.

BB This was a drum set book, an old-style drum set book where you were supposed to keep a steady high-hat and bass drum beat. There were some elaborate rhythms. They weren’t written out to be played in patterns on the set necessarily; you could just tap your foot and practice the rhythms. They were progressive and dealt with various types of subdivisions. There were other books like that – Goldenberg for example. I tried to find as much material as I could that involved syncopated patterns and triplet patterns that could be written in different ways. I was just trying to build up a vocabulary so I could understand them and sight read.

RH Did you work on these books on your own or with Mr. Street?

BB Mostly I did it on my own. What Street did was to bring things out in lessons that I couldn’t do. He never said, “Go study this or that book,” but he made it clear you should work on this or that, so I would.

RH Do you still have copies of the exercises he gave you?

BB He didn’t give them to me; he just brought things out in lessons and said, “Let’s try and play them.” They were hand manuscript.

RH I wonder if someone has them.

BB It turned out that John Beck had all of Street’s materials, or he had made copies. He and Harrison Powley recently edited and published the collection [The Complete Works of William G. Street, Fischer, 1990].

Metronome and Tempo

RH What about using a metronome? Did you use a metronome when you were young?

BB I didn’t have a metronome until I got to college, then I bought one.

RH Did you use it a lot then?

BB Not a heck of a lot. I really started working with a metronome when I started playing tabla, and it was as much for tempo as anything at that point. For me, tempo has been a big struggle in many ways. Tabla was a very intense thing to deal with in relation to tempo. When you play tabla, whether you are soloing or accompanying – especially if you are accompanying – you don’t set the tempo. Somebody starts a piece and you are playing the theka at some tempo. They finish their thing and they look at you and you’re supposed to solo in response, so you have to decide what you want to play. You have to make a decision without thinking. You wonder if what you play is going to fit at this speed, especially with the usual way of the exposition of a theme and variation. You’re supposed to play at a slow speed and double it. I would often find myself in the position where I would play the slow speed, and I thought, “Oh, this is going to be good.” Then I would try to double it and I would be screwed because I couldn’t, or I could but it was too slow. So I spent a lot of time practicing to a metronome to find those tempos. Ultimately what worked for me was…well, it’s tied in deeply with the tabla solo structure. In solo playing, one thing follows another and there are certain types of things that are supposed to happen at certain points. In general, you don’t want the tempo to slow down, you want it to keep building. I always had to figure out what the order was of the material I knew in terms of tempo, and whenever I learned something new, I had to fit it into that scheme. “Where does it sit?” Of course, it was always hard to keep that clear because I was practicing and getting better. A year would go by and the entire order would go through changes. That was a very interesting experience, and I don’t remember having it with anything else in music except for figuring out how to start the ragtime tunes in Nexus. That’s still kind of tricky for me. When I play these pieces with Nexus it’s not so much a problem because we all sort of know the tempos. Even if I don’t click them off at the right tempos everybody more or less goes at the right speed. When I play with other groups, though, it’s a big deal because they actually follow me.

RH How does one remember tempo?

BB For me it wound up being a physical sensation rather than trying to hear the piece in my head and then count it off based on that. That’s what I did at first. I would think of my part or some other part and try to hear it and then feel the time in relation to what I was hearing in my head, and then count it off based on that. I found that was pretty unreliable. Now what I find myself relating to is an internal physical feeling. Sometimes it has to do with how a basic conducting beat feels in relation to the speed for a particular piece. Sometimes it’s just that I am able to memorize the count. In fact, I try to avoid hearing the tune before I count it off because it tends to throw me off.

RH I remember Dan Hinger used to claim that he had perfect time.

BB I’ve heard about that, and I don’t doubt it.

RH I think what he meant by that is he memorized metronome markings.

BB Yeah, it’s like perfect pitch but on a different end of the continuum of frequency.

RH Do you think that is something that most people are able to develop?

BB In my opinion, people are gifted in certain ways and some people have that ability. I think it’s concerned with retention – memory. It depends on how good you are at that and I’m not good at it so it’s difficult for me. It is like other kinds of memory; you make a correspondence with something else. If you’re trying to memorize certain metronome markings and you can relate them to a physical movement that you’re familiar with – marching, walking, or if your particular gait sits certain ways for a slow walk or a fast walk – you could probably connect.

RH A mnemonic device through physical attachment.

BB I find that many people try to memorize certain metronome markings by pieces of music that they know really well.

RH Do you ever make that type of association?

BB If I don’t have a metronome and I need to find a setting, yes, sometimes I’ll do that. I might try to find mm = 120 by hearing a Sousa march, or something like that.

RH Do you advocate using a metronome for students or other musicians?

BB Yes. It’s like a feedback device. It’s a way for you to see or hear or feel where you are in relation to the time and see if you are rushing or dragging.

RH Do you think that is the best way to use a metronome – to monitor your own playing or progress?

BB Yes, I think that is the best use for it besides finding tempos. There are other devices you can work with now, like rhythm machines that play grooves. Probably computer programs do this now, too – ready-made ones. That’s a little different though. I haven’t done a lot of work that way, but that is like playing with another person.

Bodily Movement

RH You mentioned tapping your foot when you were first starting to play. Do you think it’s important to have some sort of bodily movement to instill accurate time?

BB I’ve thought about that, but I’m not sure. Some of the musicians I know who have the best time sense play tabla. They have the least bodily movement of any percussionists I have been involved with. They are very centered. They move their hands like crazy, but they are not moving much else.

RH So the great tabla players you know don’t seem to tap their feet or click their teeth or anything like that?

BB No, not that I know. I don’t know what they do internally.

RH Have you ever asked Sharda Sahai [1935-2011] what he does to keep steady time?

BB Yes, he says you develop a habit; it’s something that’s ingrained in you at a young age. I didn’t have that connection to someone with really good time when I was little. I didn’t encounter that until later in my life when I suddenly found myself playing next to somebody who had a kind of time sense that made me perk up and say, “Wait a minute, what is so beautiful about that that I don’t have?” I don’t remember that happening until later in high school, listening to some jazz records and beginning to play drum set, but it was still from a distance. When I got to Eastman and was around people like Steve Gadd and Bill Cahn, I had a different experience in relation to time feel than I had when I was little. I assume that when you are young, this sense can be transmitted to you without a lot of difficulty, but first you have to be around someone who has it, and then you can get it.

Teaching Time Feel

RH Do you think some people have it just naturally and others don’t have it?

BB I don’t know about that, but my suspicion is no. I think, however, that some people have more ability to get it or have a better aptitude for it than others. Maybe there are gifted people who just have it, but how can you tell? The question of the difference between “talented” and “gifted” is an interesting one. I believe that for certain kinds of things, time sense for example, there are certain ages, certain windows, where people can get it with very little effort. For teachers or mentors, it’s very rewarding when you can find that moment and transmit this kind of thing to a young person.

RH Do you know what these ages are?

BB Well, they’re pretty young, I assume. I began to play marimba when I was seven, and I think that was a gift. Not that I was “gifted,” but that I was given something. If you make someone start using their hands and wrists at a young age like that, they don’t have to practice a lot to get it. Suddenly you have something for the rest of your life. It’s similar to learning a language. A young person can be in a certain environment and you don’t have to teach them at all – they just learn the language. If you wait five or six years and try to do that it becomes far more difficult.

RH What about using language or speaking to play rhythms accurately? Do you think it is essential or important?

BB No, I don’t think so. I think using words with rhythms is a very useful, powerful device to help you memorize pieces, rhythms, or compositions. Maybe there is a power in that for understanding complex rhythms. I’m basing this on my experience with Indian music. The practice of clapping a beat with your hands, especially if you are clapping a beat with a pattern as opposed to just a steady clap, and speaking something relatively elaborate on top of that, for me was something that, with practice, brought a kind of confidence in how rhythmic structures work. I’m not sure it did anything to improve or change my time or rhythmic feel, but I found that it influenced my ability to remember things I was taught. To have the experience of both clapping an underlying rhythmic structure and speaking the composition was something powerful for me.

RH I know most of your teaching is with advanced students, but if you were teaching a young student, how would you introduce them to the concept of playing accurate time and rhythms?

BB I would play with them, whether it was a real duet, or even better, playing the same thing, even if it is just exercises.

RH Did your drum teacher, Jimmy Betz, do that with you?

BB No, I started doing that after Sharda [Sahai] did it with me. It is standard in North Indian teaching for the teacher or advanced students to sit and play with the younger students and not say a word about what they are supposed to learn through instruction. They just play and you do your best to keep up with them. So there is that part of it. It forces you into a state of incredible anxiety, but awareness, too. You’re really listening hard, and it makes you try to memorize as quickly as you can, otherwise you don’t get the material.

But it’s also entrainment – like that famous experiment where you put two pendulum clocks on the wall and you start them ticking out of sync, and after a few hours they will be going exactly together. It’s like a vibration gets transmitted even if it’s only by small amounts that cross the wall; somehow they get into synchronization. When you’re playing along with someone who is better than you, they somehow have a pull on you. It forces you, without you knowing or trying and as long as you are listening, to match their spacing and clarity and rhythmic accuracy. I had the experience many times where I would practice by myself and could play something at a certain speed. Then I would sit down to practice with Sharda the next day and found I could play half again as fast. I couldn’t have done that on my own, but Sharda was pulling me. It’s also a good way to learn “feel.” I don’t know if you learn it or just get it. So that is something I have done in my teaching. Even with marimba, I’ll set up two instruments face-to-face and play all the exercises with the student and have them play with me.

RH When I studied with Alan Abel as a youngster, he did that exact thing with me on snare drum and marimba for three years.

BB Did he? It makes total sense when you think about it.

RH When you are playing rhythms do you have a rhythmic grid going on in your head?

BB I don’t know; I haven’t analyzed that in myself. I’m aware of subdivision to place beats, if that’s what you mean.

RH That’s a kind of grid. I wonder if you, either consciously or subconsciously, are aware of that when you play?

BB Well, the slower I have to play in relation to a beat, the more aware I am of that. When I play faster, I’m playing at the subdivision or faster than I could divide in my head. Slow rhythms I think I divide pretty consciously.

Thinking and Playing Rhythms

RH Have you given any thought to what you think about when you play rhythms? For example, if you are playing tabla, or African drumming, or complex rhythms in Western music, do you know what your mental process is in order to play rhythms as accurately as possible?

BB In tabla, you develop a habit of hearing a melody. This comes through practicing with other musicians who, when you get to play a tabla composition, they keep a melody going. If it’s a solo tabla performance, even then, a melody is played on something. When Sharda has played solo concerts where there is just someone clapping the tal, he is often humming the melody. That creates a big structural framework, and I feel it helps with placing the rhythms as well as improvising in a big structure. It’s sort of how jazz improvisation works where you have a chord progression. This is an important thing, and I find myself trying to do it more with classical Western music or avant-garde music where the rhythm is spacious. I think of the line of the pattern or the notes, and I’m relating them to my voice and trying to hear them as a sung thing rather than trying to subdivide like crazy and place them in relation to a really fast pulse. So I’m depending on some internal clock that’s not audibly ticking, but it’s moving somehow. That’s something I’ve been getting into lately and it’s a matter of developing some trust. It’s like trusting yourself to wake up at a certain time without turning on an alarm clock.

RH What do you mean exactly when you say you’re relating the rhythms to your voice?

BB I sing them in my mind.

RH You sing the rhythms?

BB Yes.

RH Are you giving syllables to them like ta ka di mi?

BB I’m thinking of slower rhythms than that, so it would be da de dah.

RH Are you actually doing something with your mouth?

BB No, not intentionally, but I find I do sometimes if the rhythm is more precise. There are some kinds of rhythms in classical music and the kinds of rhythms we play in Nexus that are relatively defined or square and others that are more vocal or lyrical. When I’m playing rhythms that are more precise and they are fast enough that accuracy can be articulated clearly, I do sometimes click to myself.

RH Do you click your teeth or your tongue?

BB No, I click my palette. I don’t know how I do that. I do it with my nose or something; I don’t use my tongue to do it, it’s like a controlled snort. There is probably some physiological term for it. I don’t use my teeth, although I’ve been around some people who use their teeth or their tongue.

RH I don’t mean to put words in your mouth, but what I’m hearing is that you approach different rhythms in different ways to play them accurately. Maybe it depends on the style of music you are playing or a particular situation.

BB Yes. I haven’t really analyzed it, but I can see right away there are two ways, depending on the rhythmic feeling that is going on.

RH Which method do you use when you are playing African drumming?

BB Sometimes I use the click/nose thing, especially if I’m at the beginning stage of learning a pattern with which I’m not comfortable yet. A beautiful thing about learning Ghanaian music is the whole concept of conversation – getting familiar with the way any pattern I am playing fits against another pattern, including the steady beat. I try to conceptualize the pattern that way and hear and practice it, so I am really clear in my mind about the overall composite pattern that results in this drum conversation.

RH Along those lines, do you think it is necessary to fill in the gaps of a rhythm to keep accurate time – kind of like playing the ghost strokes of a rhythm?

BB I don’t know. I imagine that varies from person to person.

RH How about for you?

BB It varies for me, too. There are times when ghosting, either on the instrument or using my mouth sounds to fill up a space, works well for me, or when it just feels good to do it – but not always. When I feel really confident about a pattern, I don’t feel like I need to do that.

RH In developing that confidence might you have used that system?

BB Yes.

RH Can you remember or describe instances when you might or might not have used that system?

BB The concept of ghost strokes was something I knew nothing about until I started playing with John Wyre – he’s Mr. Ghost. What I liked about it from him is that he did it as an accompaniment device to give whomever he was playing with a hint. “Here’s where I am placing it, and this will help you place your sound or stroke.” Jazz drummers are good at that; they use the device a lot. It’s something I have started to incorporate into my playing, but it’s relatively new for me.

RH Have you ever tried to hear the spaces between attacks of a rhythm as a rhythm itself?

BB Wow! Yes, but when I have done that it has been pretty contrived; I’ve had to really work at it.

RH By contrived, do you mean it didn’t just pop out at you?

BB Yes. It was something I knew intellectually was a phenomenon, and I could pay attention to it.

RH Can you remember any rhythms with which you’ve heard the spaces as a rhythm?

BB The first time I remember doing that was playing paradiddles on two different surfaces – one stick on a semi-silent surface, but that was just an effect or a curiosity.

Tabla and North Indian music

RH How would you define tala?

BB Tala has two traditional meanings, at least in North Indian music. One is a big, general concept of all rhythmic activity in the music. That’s tal. It has a broad sense including all those terms we were just talking about. But it also has a more specific meaning which is the particular rhythmic cycle, and that is defined by a number of things. These specific tals have names, and they have a fixed number of beats called matra. There is some question about the exact definition of matra, too. In 4/4 time in Western music, the beat is a quarter note. In tal, if you have a sixteen beat tal you have sixteen matras, and each matra can be subdivided, of course. Then you have to organize those matras into some grouping. So, it’s a little like meter, but it’s not necessarily the same. It could be grouped 5, 4, 3, 2, 2 or it could be grouped 4, 4, 4, 4. Those are two things about tala, and then there is a third thing called theka. You need all three of those things, and you have to know all three to say this is such and such a tal.

RH Is one aspect of tal that it is a rhythmic cycle?

BB Yes.

RH What is theka?

BB Theka is specific drum sounds or strokes that define each matra in the tal. Each beat gets a stroke. Some beats get the same stroke, but there is a specific one for each beat and they don’t get changed around.

RH Taking into consideration what you said about rhythm, would you consider rhythm to be flow or an interruption of flow?

BB It’s organization of flow. Interruption is an extreme word, although that is an interesting concept. I would say that the time flows and rhythm organizes it. In that sense, rhythm is flowing, too, but rhythm is organizing something else that is already flowing.

RH That’s good!

BB Thanks, I finally got something good.

RH Do you think the terms we have in Western music for aspects of rhythmic theory are adequate to describe all aspects of North Indian rhythmic theory?

BB I think we have equivalent terms except maybe for theka. The closest thing I can think of in Western music would be the standard ways a jazz drummer would play 12-bar blues for example, but theka is more standardized than that.

RH There’s no term in Western rhythmic theory for that?

BB Well, maybe there is, but I’m not deeply enough into the jazz world. They might have a phrase for it, I’m just going by what I’ve heard. There are points in certain measures in the sequence of the chord progression of a 12-bar blues that usually have an accent somewhere off the beat in a certain way. This is unlike North Indian music where you emphasize the first moment of the first matra of the tal. In jazz, that’s exactly what you don’t want to do, although you are expected to elaborate on it, which is the same thing tabla players do with theka. Tabla players have specific points where they play a stroke, but they are expected to elaborate on that as it goes along. It’s a real art to do that beautifully.

Rhythmic Notation

RH Do you think Western notation is a help or a hindrance in playing accurate rhythms with good time?

BB I don’t think it matters; it’s not an issue. Playing good time is something you get from other people. It’s not a question of getting it from notation or having the notation get in the way.

RH In order to play rhythms accurately, is it better to learn them with or without notation?

BB Those are two different things. Good time is one thing and playing rhythms accurately is another. I can’t really give a universal response to that because I grew up my way and I learned the way I learned.

RH But you’ve learned both ways. You learned tabla without notation.

BB Yes, but I learned notation before learning tabla, so it was there lurking in the background.

RH How closely was it lurking? When you learned rhythms on tabla were you visualizing notation?

BB Yes, because the first teacher I had, Gnan Gosh, right from the very first lesson, wrote things on a blackboard using his own notation system. A notation system is something that has been part of North Indian music for close to a century now. It’s a system that a couple of Indian music theorists developed based to some extent on Western staff notation, although it’s a kind of strange version of that. Their system is similar to the way you and I used to notate our tabla lessons in which you make a bracket and everything within the bracket would be equal. We underlined within the bracket if we wanted to make rhythms, and it was all very clear. It works just like notes with stems and beams, etc. I started using that system right away and got into the visualization approach. I could relate to it because of the similarity to Western notation. I don’t think this is true of most tabla students in India.

RH Even now, do you visualize notation when you play tabla?

BB No, I don’t. But when I play The Downfall of Paris, I don’t visualize notation either. With tabla, in my mind I’m hearing the syllables I was taught to play. But that’s only up to a point because you can’t articulate all that when you are playing really fast, you have to slow down your thinking. Then, I’m probably thinking of numbers more than anything; trying to stay aware of how the phrases add up in larger groupings.

RH When I play The Downfall of Paris, I’m not sure if I’m thinking of notation.

BB What about Three Camps? I’m certainly not thinking about notation when I play that.

RH I might be thinking of notation on some level, especially since I learned it with notation. If I had learned it aurally, it would be different. A closer correlation for me is African drumming. I learned patterns aurally and played them for a long time before I even attempted to write them down, but it’s hard to know.

BB Yes, it is.

Rhythmic Grouping

RH Do you think there might be some physical or biological reason why our bodies react to 8-bar groupings rather than some other groupings?

BB That’s possible, although I wouldn’t assume that. I think what is much more potent is what we are brought up with and what we hear around us all the time.

RH Do you think it is possible if we were brought up with 5 as the base we would all feel comfortable with 5?

BB Sure.

RH Do you think all rhythms can be reduced to groupings of 2 and 3?

BB Not all rhythms. With the general rhythmic material that we encounter in most of our music and certainly in classical music up until fifty years ago, and most pop music and most rational rhythms, I would say yes.

RH Do you think it is possible to think of a group of 5 purely as a group of 5 and not as groupings of 2+3 or 3+2?

BB Yes, I can feel it purely as a group of 5, but it’s always reducible, one way or another.

RH Are you able to feel a grouping of 5 purely as a group of 5 because of your training in Indian music?

BB I don’t think so. Anyone who works with playing these groupings can get comfortable with them and feel them that way.

RH Bill Cahn says he was at a rehearsal at Eastman playing music of Edgar Varèse. Varèse was sitting right behind Bill, and at one point said to him, “No, it’s 5. Not 2+3, but 5: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.”

BB I can understand what that would mean. My experience with Indian music is that there is more of a tendency to group, and that’s because there is always syllable content which tends to create some sort of an effect. Even in tabla, if you had dha dha dha dha dha, you wouldn’t have anything to go on, but the phrases generally are not like that. Even if it as simple as te te te te it still implies an alternation, so you would feel a grouping. With Ionisation, or some other Varèse piece where you have those patterns, I can understand the desire for a flat feel.

Origins of Tabla

RH What is your understanding of the dates of the origins of tabla?

BB This is a subject of debate, especially when tabla players themselves are in on the conversation. It seems like it was in the mid-eighteenth century when the tradition really started to gel and players began creating their own repertoire and working intensely to develop style.

RH Jim Kippen has written extensively on this topic and is still researching it. [Note: James Kippen, in his book, Gurudev’s Drumming Legacy, published in 2006 by Ashgate Publishing, outlines a thorough history of tabla. In Kippen’s article “Rhythmic Thought and Practice in the Indian Subcontinent,” in The Cambridge Companion to Rhythm, Cambridge University Press, 2020, he summarizes the history of tabla and provides an overview of both North Indian (Hindustani) and South Indian (Karnatak) rhythm.]

BB Yes. Sharda’s chronology, based on his family’s background, seems to support that. The instrument could have been invented in the seventeenth century, maybe even earlier, but it is hard to know what really happened. It could have been more of a folk instrument for a while.

RH I was surprised to read that tabla is such a recent instrument.

BB Yes. It is amazing, given the amount of material that has been composed and the way the technique is so advanced and so elaborate. But then, when was the piano invented?

RH Around 1700, I think.

BB And it has an enormous repertoire and highly-developed technique. Of course, the piano has keyboard ancestors that are similar, and so does tabla. There are drums like the pakhavaj that have a similar playing technique.

Tabla Composition

RH How are tabla compositions composed?

BB If you ask Sharda that question, and maybe you already have, he will say they all come from God. [I asked Sharda that question and he said the compositions are God-gifted.] Yes, I asked him recently if he had been doing any composing, and he said he had been trying. So he composes. He has given me a few pieces that he composed for me.

The way I see it is you can create a composition based on a previous one that some famous tabla player perhaps composed, and you can make something similar to it – a variation on it. That’s one way. Then you can have this experience that he is talking about when he says they come from God. I’ve had this same experience – I don’t know if it is exactly what he is talking about – but I assume it is. When I was really practicing hard on tabla, spending several hours a day thinking about it, I would go to bed some nights thinking about tabla compositions. They would be going through my mind all the time. Musicians experience this often. Or I would wake up in the middle of the night and something would be going through my mind. At the height of that time in my life, it happened to me that I would wake up with a complete piece in my head. I would get up and write it down.

RH A complete new piece?

BB Yes, a couple of them. This happened maybe half a dozen times and it was remarkable in the way the structure worked. There would be unusual tihais, for example, that I may have known from other compositions with a similar structure, but they would be in triplets instead of sixteenths. So to compute it would be very difficult, let alone come up with phrases that worked. My subconscious mind invented these things and I thought that was pretty cool.

These experiences happened when Sharda was back in India and I hadn’t seen him for a while. On my second trip to India, I had a few of these compositions with me, or at least I knew them by heart. I played one of them and I said, “What is this composition?” because I didn’t know if it was a gat or a tukra or something else. Sharda said, “Where did you get this?” I said I woke up one night and it was in my dreams. He said this composition was by Ram Sahai [founder of the Benares gharana, or school, of tabla playing]. I don’t know if Sharda was saying that it was Ram Sahai bestowing something on me or if it was a composition that Sharda actually recognized, something that he knew. I don’t think it was something that he knew.

RH Do you think it was similar to a composition that Sharda knew?

BB Yes, I think it was like that, but Sharda took the composition seriously and he also took my experience seriously. I recited the other ones that had come to me that way, and he said, “Now you have this,” then he played another composition. As it happens, there is a certain kind of tabla composition that is traditionally written in pairs. The two pieces are similar with some use of phrases or rhythmic effects that are present in both compositions. However, they are varied in some interesting way. This style is called jori, and often the teacher won’t teach the student both compositions; they will give one to one student and one to another. If students learn both pieces, they feel like they are really in on something special. Sharda knows many of these jori, and he had taught me one of the two versions. When I woke up in the night, I had two pieces, and Sharda said, “Oh, very good!” In response to all this he taught me other compositions in the jori style, so it was a great feedback experience. I felt I had a taste of how the great tabla players compose. They don’t sit down to write a composition and try different phrases and say, “How am I going to make this work?”

RH Like Western composers do.

BB Yes. Instead, it’s on your mind. You are thinking about it so much that when your conscious mind shuts down, your subconscious keeps going. Another example of this is when you are trying to solve a problem and spend a lot of time thinking about it but can’t come up with a solution. Then one day you wake up and say, “Oh, yeah!” My guess is that process is similar to the way tabla players compose.

RH Have you learned any secret tabla compositions?

BB Yes.

RH Have you noticed any difference between the secret compositions and the non-secret?

BB A lot of times the secret compositions are longer; they tend to be bigger compositions. There are different levels of secrecy, too, as I understand it. Indian musicians talk about thread, milk, and blood. That describes three levels of relationship you can have, and it probably goes beyond music, too. Thread indicates a disciple – someone who has tied the thread in a ceremony where a guru accepts a student. That puts teachers in a position to make certain demands on their disciples, but disciples can expect certain things from their teachers too. These disciples can learn enough to make a living as a full-fledged musician. Blood is the next level, and that could be a family member. Maybe you marry your teacher’s second daughter; that puts you in a blood relationship with your teacher, and the chances are that you will get some secret material. By secret I mean that teachers wouldn’t give it to their normal disciples. Then the milk one is if it is your own son or daughter. If you are at that level, you are in a position to get almost everything. How they decide what is the most secret material, I’m not sure. I think it has to do with who composed the piece in the first place. For example, Sharda knows quite a few compositions that were composed by his ancestor Ram Sahai, the founder of the Benares gharana. Those compositions are closely guarded, in fact tabla players will rarely play them in public, even in a concert. They don’t want other people to learn them. It’s weird, but it’s like their form of copyright.

RH So there is nothing intrinsically different about the rhythms in these compositions?

BB Not that I’ve been able to perceive. The compositions I have learned that are supposed to be extra special tend to be more elaborate. They often have some kind of quirky thing in them, but they are not necessarily complicated.

RH Something that is just a little different than normal?

BB Yes, and really clever or beautiful.

Special Powers of Rhythm

RH Do you think there are tabla compositions that have special powers.

BB Yes, and I have been given a couple of those. Supposedly the story is that if you play them perfectly then something unusual will happen.

RH Like what?

BB An example is that if you play with a coconut in front of you, you can crack the coconut. Or you can blow out a candle flame across the room. Another one is supposed to influence animals. There are particular ones to certain gods, like Ganesh, the elephant god. Supposedly if you play a Ganesh composition perfectly, elephants will respond in some way.

RH Have you ever experienced one of these unusual occurrences when a tabla composition was played?

BB I have never experienced anything physical like that in tabla playing.

RH Anything non-physical?

BB Well, any kind of music can move you. I’ve had that kind of experience with almost every kind of music I have been involved with. The most out of the ordinary experience I can remember is some performances with Abraham [Adzenyah, our West African drumming teacher at Wesleyan University]. Sometimes when we played Akom, a spirit possession dance, I felt like I was losing it and had to catch myself.

We were playing in a dance club in New York City, and the place was packed with people. We played Akom and Abraham was really getting into it. I don’t know if he was pretending to be possessed or whether it was really starting to happen, but I felt it, too. I felt the energy and the entrainment effect was palpable. For better or worse, I resisted it, but it would have been interesting to go with it, but I didn’t know how, so I didn’t.

RH Do you think it was just feeding off Abraham’s energy?

BB I think so, and the energy of the whole vibe in the space. If he had done the same thing with another piece, like High Life, it could have been the same.

RH Do you think there are certain rhythms or rhythmic pieces that can invoke an altered state of consciousness?

BB I think it’s more how we relate to what is going on around us and how in tune you can be with the music. I can imagine other aspects of life that can produce an altered state of consciousness just because you were so involved in it emotionally, but I don’t think it is because of rhythm or melody per se.

RH So you don’t think there are rhythms that can create this effect?

BB Objectively, no I don’t think so. Even in the case of African music that is intended for spirit possession, I think it affects certain people more than others. The spirit mediums are the ones who can really be possessed. My take on it is that some people are more sensitive to it and can become involved more deeply. But the music, the rhythm, the preacher, or whoever is acting or creating the activity is important. A person must develop an affinity and a love for and sensitivity to the practice to be affected. Or maybe it is just a gift that they have.

RH Are there any rhythms in particular that fascinate you?

BB What I find the most moving and fascinating is the kind of feel that certain players can put into a rhythm, any rhythm. I went to a gospel church in Toronto a while back where there were half a dozen gospel choirs with great drummers and great singing. There was one drummer who didn’t play anything special – nothing that the other drummers weren’t playing – but as soon as he started to play, I was incredibly moved, and I think most people in the church felt it, too. It was the way he played time.

RH It’s the time feel that affects you more than the rhythms.

BB Yes, a lot more.

RH I had a similar experience in Ghana. Every morning I attended a rehearsal of the Ghana National Dance Ensemble at the University of Ghana in Legon. This was a troupe of drummers and dancers selected from the best musicians all over Ghana to promote the cultural heritage of the country. They learned and performed the dance music of all the different ethnic groups in Ghana. There was a very tall Dagomba drummer [I later found that he was probably Abubakari Lunna, the great lunna or hourglass-shaped talking drum of the Dagbon people of Northern Ghana] who occasionally played the bell part in some of the Ewe and Akan dances. In spite of the fact that all the drummers in the ensemble were fantastic players, each with a great time feel, when this man played the bell, the music reached a new level of excitement. It was the way he played time that made this happen.

BB Maybe that effect is quantifiable; maybe there is a way to objectify it with computer analysis and figure it out, I don’t know. Or maybe it is magic. I don’t have it, that’s for sure.

Bob Becker’s Compositions

RH I think you do. I want to ask you about your own compositions. How have you used rhythm in your own compositions?

BB My first interest was to try and incorporate the kinds of rhythmic formulas that are used in tabla in music that I write. I initially did that with Palta and with Lahara, the big snare drum solo. The idea with Palta was to take a tabla player and put them in a context where they would feel comfortable playing the traditional tabla repertoire but accompanied by Western instruments so there would be interaction between an Indian drummer and percussionists who were trained in Western music.

With Lahara I was interested in trying to take material I learned on tabla and realize it on a drum that I could play in a traditional way with which I was familiar – like you did with mrdangam in your PhD dissertation. That was a lot of fun to work with and see what things were translatable from one to the other and find a methodology for making that translation. It was finding rudiments that felt right for certain tabla phrases. It is an arrangement rather than a transcription. I tried to find my own feel with each kind of phrase, for example finding a phrase on tabla that had seven notes ending with an accent. When I played it on tabla it would feel a certain way, and when I played it with sticks on a drum, I would try to make it have a similar feel but without the same alternation of hands.

RH It’s an adaptation.

BB Yes. In Palta, I was interested in finding a way to use harmony to clarify the structure of a tal rather than necessarily a melody. In a way, that’s getting back to this harmonic rhythm idea we just discussed in which a change in harmony makes clear the structural points of a big rhythmic cycle. I could then, at that point, eliminate the need for drum syllables or anything like that and substitute melodies that were more typical of Western music or jazz. If there is anything rhythmically unusual about what I’ve written in the past eight years or so, it would be making the structural transition from a melody, a long melody that defines the structure, to a drum with admittedly quite a few tonal characteristics, but nevertheless something that could not play a melody or a harmony, and playing the drum against a long melody.

Another interesting thing I wanted to explore was to bring in harmony from Western music and let it establish a harmonic rhythm, then using a melody against it in a way that is more typical of Western music. I’m still interested in cycles of different lengths going against each other and fitting them into an overall large structure of some number of beats. Music I write is more concerned with harmonic evolution than with any particular rhythmic concept, although I do rely on the number five in the music a lot. This is because the material for melodies and harmonies comes from a five-tone raga.

RH I was going to ask you why many of your pieces are in five.

BB The reason they are in a rhythm of five is that five is a very ambiguous sound to me. Even more than seven or other relatively small prime numbers, five is the most mysterious. When the rhythms are very square and you organize them into long groups of five, or some multiples of five, they tend to surprise me, so I go with that.

RH Have you consciously tried to stay away from working with small rhythmic figures as part of the basic structure of your compositions or did it just happen?

BB It probably just happened. I’m interested in the small figures in terms of development because that’s something I’ve spent a lot of time with on tabla in relation to kaida and rela theme and variation forms. These forms are based on relatively small patterns that are developed into grandiose pieces as a result of expanding them. The piece I wrote for orchestra last year [Music On The Moon] is based on this kind of motivic development. It has a few relatively small motives that are significantly elaborated and form the basis for the whole piece. [Note: In Bob’s article, “Finding a Voice,” in The Cambridge Companion to Percussion, Cambridge University Press, 2016, he describes his compositional process in more detail.]

RH What are some composers whose music you find rhythmically interesting?

BB Steve Reich has been a source of intrigue and inspiration; I’ve learned a lot playing his music. I like Chopin and his concept of elasticity, phrasing, and the way he squeezes an irrational number of notes into a beat – it’s not irrational. I love Richard Strauss, and I think that has to do with his use of rhythm. Your question makes me think of composers I like in general.

RH What composers do you like?

BB I like Debussy a lot. It may sound strange, but I like Schoenberg’s music. I’m not attracted to Carter and Boulez, composers whose work is rhythmically complex. To serialize rhythm is an incredibly intellectual way to deal with rhythm and I have trouble keeping up with it. At those points where the rhythmic structure becomes incomprehensible, I lose interest. I enjoy elaborate complexity more if I can hear what it is doing. On the other hand, I think John Cage’s percussion music is great. It is rhythmically complex, but complex in a slightly naïve way. Maybe that relates to me in a way.

RH What about Stravinsky, you didn’t mention him.

BB Early Stravinsky, sure. I don’t find his later music as interesting rhythmically.

RH Do you think there is a rhythmic system that is applicable to all musical cultures?

BB I don’t think so. Maybe the question should be are the rhythmic systems in all musical cultures based on the same thing, and I don’t know the answer to that question. In Japanese music, for example, the rhythm is abstract to me, so it is difficult to see how it has the same underlying basis. It comes back to time. If time is at the heart of it, then at a very basic level there would have to be some system for the rhythm across all musical cultures that has the same base.

RH What questions about rhythm that we haven’t discussed interest you?

BB I would like to know more about the neurological basis for rhythm – what part of the brain is active when rhythmic perception is taking place. Taking it further, I would like to know how the perception of musical rhythm relates to how rhythm is processed in other ways. For example, how are you able to wake up when you need to without using an alarm clock. And then, what is the mechanism that makes it possible for some human beings to play with accurate time? What is that clock? There must be something physical happening at a chemical or cellular or electrical level somewhere in the body. There must be something there ticking that makes it possible to do it and hear it.